Study: PHEVs aren’t plugged in as often as regulators assume

Plug-in hybrids only achieve their maximum emissions benefit when they are actually plugged in daily, and that isn’t happening as often as regulators who set emissions rules assume, according to a new study from the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT).

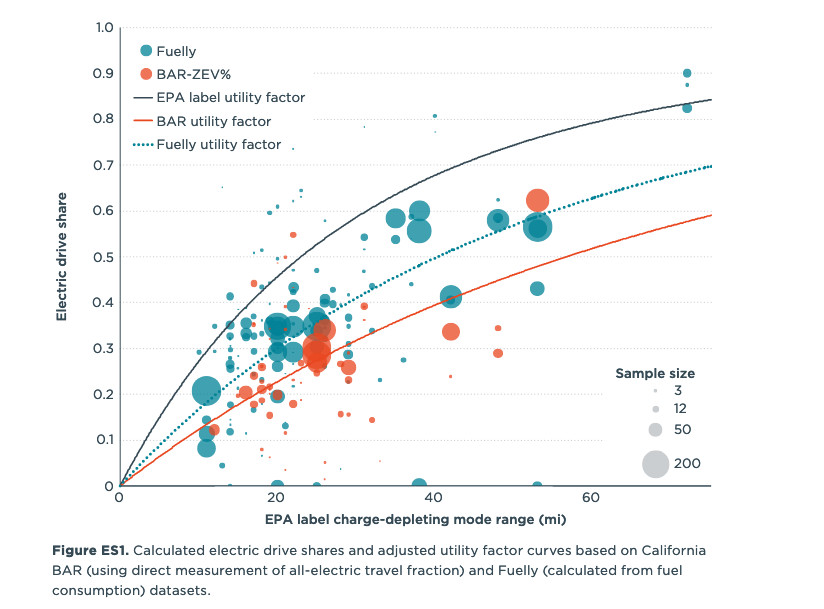

Based on self-reported fuel economy figures from the website Fuelly.com and data for engine-off distances traveled collected by the California Bureau of Automotive Repair (BAR), the study found that real-world electric miles driven by plug-in hybrids may be 25%-65% lower, and fuel consumption 42%-67% higher, than EPA-sanctioned window-sticker labels.

Plug-in hybrid electric driving versus EPA electric-range ratings (from ICCT study)

Drivers need to maximize the amount of electric miles by plugging in frequently, but unlike all-electric cars, charging isn’t mandatory. Plug-in hybrids can still be driven solely on gasoline power, which might prove more convenient for drivers but also increases fuel consumption. Early adopters likely have more access to charging, while mainstream adopters can’t be assumed to plug in as often, the study concluded.

To remedy this, the ICCT recommends looking at actual electric miles driven to inform regulatory decisions, arguing that the EPA could generate this data “through on-board diagnostic reporting requirements.”

The ICCT also recommends setting minimum electric range requirements for plug-in hybrids, similar to California’s range requirements for zero-emission vehicle credits under its Advanced Clean Cars II standard. Future California regulations will require 50-mile plug-in hybrids based on certain test cycles, which may result in a range of market choices offering in the vicinity of 40 electric miles or more, something only a handful of plug-in hybrids like the Toyota RAV4 Prime offer today.

2023 Kia Niro plug-in hybrid

Analysts also suggested requirements like minimum all-electric power and cold-weather performance, maximum gas tank sizes, and mandatory fast-charging capability that would nudge plug-in hybrids further in the electric direction.

This isn’t the first analysis to question the emissions benefit of plug-in hybrids. A report from the environmental group Transport & Environment in 2020 found that real-world emissions from plug-in hybrids in Europe are also considerably higher than official ratings. European regulators have since considered ending the plug-in hybrid era early to concentrate on all-electric cars.

In the U.S., buyers now have many plug-in hybrid choices, particularly from Volvo, which eliminated standalone gasoline engines from its lineup for 2023. Consumer Reports has also found that plug-in hybrids, along with hybrids, are factoring in as more reliable than EVs.

Add a comment Cancel reply

Related posts

EV Guide: How to Care for Your Electric and Hybrid Car